What is Gosplan’s Role in Market Economics?

Gosplan, officially known as the State Planning Committee of the Soviet Union, represents one of history’s most ambitious attempts to replace market mechanisms with centralized economic planning. Understanding Gosplan’s role in market economics provides crucial insights into how command economies function, their inherent limitations, and why market-based systems have become dominant globally. This historical examination reveals fundamental principles about resource allocation, efficiency, and economic coordination that remain relevant to modern business strategy and market dynamics.

The study of Gosplan extends beyond historical curiosity—it illuminates critical differences between planned and market economies, offering valuable lessons for contemporary policymakers, business leaders, and economists. By exploring how Gosplan attempted to manage an entire economy through directive planning rather than price signals and consumer choice, we can better understand the mechanisms that drive modern markets and the importance of stock market mechanisms in efficient resource allocation.

Understanding Gosplan: Definition and Historical Context

Gosplan emerged in 1921 as the Soviet Union’s primary instrument for economic management, replacing what leaders viewed as the chaotic and inefficient market mechanisms of capitalist economies. The acronym stands for “Gosudarstvenniy Planoviy Komitet,” reflecting the communist ideology that centralized state planning could allocate resources more rationally than decentralized market forces. Unlike modern markets near me that operate through price discovery and competition, Gosplan operated through directive quotas and production targets handed down from Moscow’s central authorities.

The organization functioned as the supreme economic coordinator, responsible for determining what goods would be produced, in what quantities, at what prices, and how resources would be distributed across the entire Soviet economy. This represented a radical departure from market economics, where individual consumers and producers interact through voluntary exchange. Gosplan’s architects believed that scientific planning could eliminate the waste, unemployment, and inequality they associated with capitalism, creating a more efficient and equitable economic system.

The historical context of Gosplan’s creation is essential for understanding its role. Following the Russian Revolution and civil war, Soviet leaders inherited an economically devastated nation. The New Economic Policy (NEP) of the 1920s had temporarily allowed limited market mechanisms, but Stalin’s rise to power brought a decisive shift toward complete centralization. Gosplan became the institutional embodiment of this shift, tasked with rapid industrialization and the transformation of a largely agricultural society into an industrial superpower.

How Gosplan Functioned as a Planning Mechanism

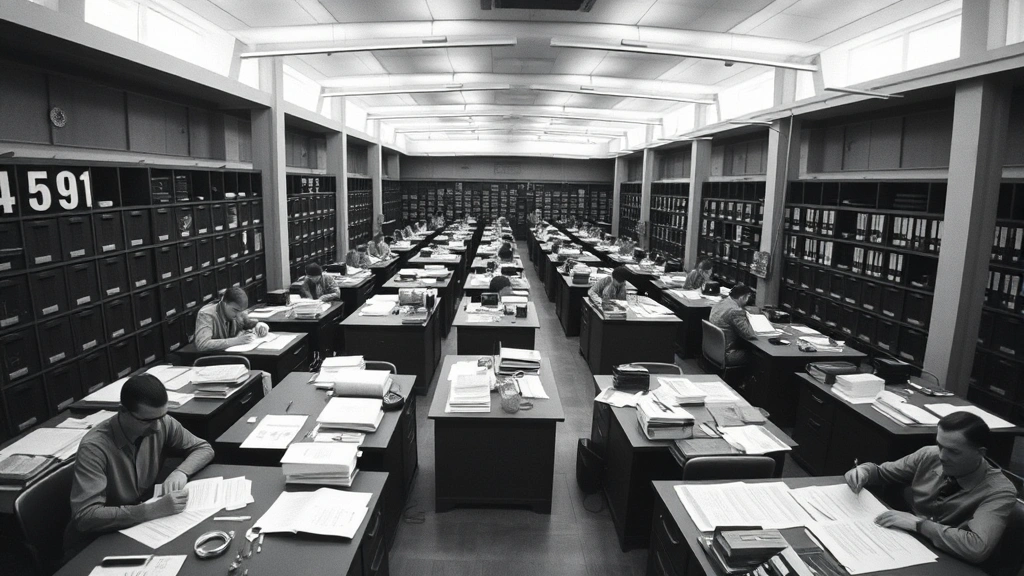

Gosplan’s operational structure represented an unprecedented attempt to coordinate an entire national economy through administrative directives rather than market signals. The organization employed thousands of economists, engineers, and statisticians who worked to create comprehensive five-year plans detailing production targets for every significant enterprise across the Soviet Union. These weren’t suggestions or guidelines—they were binding mandates that factory managers and agricultural collectives were legally required to fulfill.

The planning process began at the top with political leadership establishing broad economic priorities and growth targets. Gosplan would then disaggregate these national goals into sectoral targets, which were further broken down into regional and enterprise-level quotas. Each factory received specific instructions: produce exactly 10,000 tons of steel, or manufacture 50,000 pairs of shoes in a particular size range. This hierarchical system attempted to create perfect coordination without relying on prices or profit signals.

Crucially, Gosplan also set administered prices for goods rather than allowing market competition to determine value. These prices bore little relationship to actual scarcity or production costs. A loaf of bread might be priced artificially low for political reasons, while consumer goods faced arbitrary markups. This price-setting mechanism created constant shortages and surpluses, as the signals that guide market rise hub blog discussions of modern economics were completely absent from the Soviet system.

The organization maintained elaborate statistical systems to track plan fulfillment, though these systems became notorious for distortion and falsification. Managers facing impossible targets would manipulate production figures, report inferior goods as high-quality, or shift resources from one area to another to meet their quotas. These perverse incentives meant that Gosplan’s actual information about the economy became increasingly unreliable, undermining the entire rationale for centralized planning.

Gosplan Versus Market Economics: Fundamental Differences

The contrast between Gosplan’s command approach and market economics reveals fundamental principles about how economies coordinate activity. In market economies, prices serve as information signals that communicate scarcity and desirability to producers and consumers. When demand for a product increases, prices rise, signaling producers to increase supply. This decentralized feedback mechanism requires no central authority directing production—millions of independent decisions aggregate into a functional system. Understanding these principles is essential for anyone involved in digital marketing strategy examples and modern business operations.

Gosplan, by contrast, attempted to replace these price signals with administrative directives. Central planners, no matter how intelligent or well-intentioned, lacked the information dispersed throughout society about individual preferences, local conditions, and technological possibilities. As economist Friedrich Hayek argued, the knowledge problem inherent in centralized planning made it impossible to achieve efficient resource allocation. A local manager knew conditions in their factory; consumers knew their preferences; workers understood their capabilities—but this vital information couldn’t be aggregated through bureaucratic channels.

Market economies also harness incentives differently. Profit motive drives innovation and efficiency; businesses that waste resources or ignore consumer preferences fail and exit the market. Gosplan-directed enterprises faced no such discipline. Meeting quotas mattered more than satisfying actual human needs. A factory could fulfill its production target by manufacturing low-quality goods, and the manager would still receive a bonus. This created persistent quality problems and misallocation of resources toward politically favored sectors regardless of actual demand.

Furthermore, market economies enable experimentation and adaptation. New businesses can emerge; unsuccessful ones can fail; resources flow toward uses that consumers value. Gosplan’s rigidity meant that once a plan was set, adapting to changed circumstances proved difficult. If technological advances suggested new production methods, or if consumer preferences shifted, the system lacked mechanisms for rapid adjustment. This inflexibility became increasingly problematic as the Soviet economy matured and competition from more dynamic market economies intensified.

The Limitations of Centralized Planning

Despite its theoretical elegance, centralized planning under Gosplan faced insurmountable practical limitations that became increasingly apparent over decades. The knowledge problem proved fundamental and insurmountable. A central planning authority, no matter how large its staff, simply couldn’t possess the detailed information necessary to make millions of production and allocation decisions efficiently. Local knowledge about specific conditions, technological possibilities, and consumer preferences remained dispersed throughout society, inaccessible to central planners.

The incentive problem compounded these difficulties. Without market discipline, enterprises had little motivation to minimize costs or improve quality. The famous Soviet joke—”They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”—captured the reality that without profit motive or competitive pressure, productivity growth stagnated. Workers faced no consequences for poor performance; managers received bonuses for meeting quantitative targets regardless of quality or actual usefulness of output. This meant that even when Gosplan correctly identified what needed to be produced, execution remained inefficient.

Innovation suffered dramatically under this system. Market economies generate continuous pressure to develop new products and processes that reduce costs or better satisfy consumer needs. Gosplan’s enterprises had no such incentive. Innovation required resources and entailed risk, and the quota system rewarded meeting targets with existing methods rather than investing in uncertain improvements. Consequently, Soviet technology fell increasingly behind Western competitors, particularly in consumer goods and advanced industries.

Shortages and surpluses became chronic problems that Gosplan couldn’t resolve. Because prices didn’t reflect actual scarcity, some goods disappeared from shelves while others accumulated in warehouses. The famous Soviet experience of queuing for basic goods while luxuries sat unsold illustrated the dysfunction. A functioning market would adjust prices to clear supplies, but Gosplan’s administered prices remained fixed, creating perpetual imbalances.

The system also proved vulnerable to what economists call the “ratchet effect.” Once an enterprise demonstrated it could produce a certain quantity, planners would increase future targets. This encouraged managers to hide productive capacity, underperform, and resist innovations that might increase their baseline targets. The perverse incentives meant that Gosplan’s information about actual capabilities became systematically distorted, making planning even more difficult.

Gosplan’s Economic Impact and Performance Metrics

Evaluating Gosplan’s economic performance requires examining both its successes and spectacular failures. In the early decades, particularly during rapid industrialization in the 1930s, Gosplan achieved impressive growth rates in heavy industry. The Soviet Union transformed from a largely agricultural society into an industrial power, producing steel, coal, and machinery at scale that impressed contemporary observers. These achievements came at enormous human cost—collectivization caused famines killing millions—but they demonstrated that centralized planning could mobilize resources for specific objectives.

However, these gains came from mobilizing previously underutilized resources rather than from efficient allocation. The Soviet Union had vast labor, raw materials, and capital that market mechanisms hadn’t fully developed. Directing these resources toward heavy industry through planning could generate growth, but this growth model became exhausted as the economy matured. By the 1970s and 1980s, Soviet growth rates had declined to levels comparable with or below Western economies despite central planning’s theoretical advantages.

Comparative analysis reveals Gosplan’s fundamental problems. Soviet citizens enjoyed lower living standards than comparable Western populations despite similar or greater resource endowments. Consumer goods remained scarce and low-quality; technological advancement lagged behind market economies; and labor productivity growth stagnated. Research from institutions like the RAND Corporation documented how Soviet economic performance deteriorated relative to market economies as both systems matured.

The statistics Gosplan produced became increasingly unreliable as the system aged. Managers falsified reports to meet impossible targets; double-counting of goods was rampant; and quality metrics were manipulated. This meant that by the 1980s, even Soviet leaders lacked accurate information about their economy’s actual condition. The system had become so distorted that central planners were making decisions based on fiction rather than reality.

Agricultural performance under Gosplan proved particularly disastrous. Despite the Soviet Union’s vast agricultural resources, chronic food shortages plagued the system. Collectivization destroyed incentives for productive work; central planners lacked detailed knowledge about local agricultural conditions; and the price system provided no signals about which crops to emphasize. The contrast with market economies, where agriculture became increasingly productive, highlighted centralized planning’s failure in this sector.

Lessons for Modern Market Economics

Studying Gosplan provides invaluable lessons for understanding modern market economics and the importance of marketing strategy for small businesses in competitive environments. The knowledge problem Hayek identified remains central to economic organization. Markets harness dispersed knowledge through price signals, enabling coordination without central authority. This principle applies beyond Soviet-style planning to any situation where information is dispersed and decisions are decentralized.

The importance of incentives cannot be overstated. Gosplan’s failure to align incentives with desired outcomes demonstrates why profit motive and competitive pressure matter. When individuals benefit from efficiency and innovation, they pursue these goals relentlessly. When they face no consequences for poor performance, productivity suffers. This principle explains why why marketing is important for business success—it aligns organizational interests with customer satisfaction.

The Gosplan experience also illustrates why flexibility and adaptation matter for economic success. Markets enable rapid response to changed circumstances; new businesses emerge to exploit opportunities; unsuccessful ventures exit. Centralized planning’s rigidity meant that Soviet economy couldn’t adapt quickly to technological changes or shifting consumer preferences. Modern businesses must maintain similar flexibility, constantly monitoring market conditions and adjusting strategies accordingly.

Furthermore, Gosplan’s history demonstrates the limitations of technocratic solutions to economic problems. Even with the best intentions and considerable expertise, central planners couldn’t replicate the efficiency of decentralized markets. This suggests humility about what any organization—public or private—can accomplish through top-down direction. Modern management theory increasingly recognizes that organizations function better with distributed decision-making and clear incentives than through rigid hierarchical control.

The quality and innovation problems that plagued Gosplan remain relevant to modern management. Organizations without competitive pressure or profit incentives struggle to maintain quality and drive innovation. This explains why competitive markets produce superior outcomes to monopolies, and why internal competition within organizations can improve performance. Understanding these principles is crucial for anyone studying stock market dynamics or modern economics.

Finally, Gosplan’s reliance on distorted information and falsified statistics demonstrates the dangers of disconnecting decision-making from reality. Organizations that ignore accurate feedback about performance inevitably deteriorate. Markets provide harsh but honest feedback through profit and loss; businesses that ignore customer preferences or waste resources fail. Systems that can ignore or distort feedback—whether communist planning or insulated bureaucracies—tend toward dysfunction and eventual collapse.

FAQ

What exactly was Gosplan and when did it operate?

Gosplan was the State Planning Committee of the Soviet Union, established in 1921 and operating until the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. It functioned as the central authority responsible for planning the entire Soviet economy through five-year plans and directive quotas, replacing market mechanisms with administrative coordination.

How did Gosplan differ from market-based economic systems?

Gosplan used centralized administrative directives to determine production and distribution, while market economies rely on price signals and competition. Markets coordinate through decentralized decisions by millions of actors; Gosplan attempted coordination through top-down planning. Markets use profit incentives; Gosplan used quota fulfillment targets.

Why did centralized planning under Gosplan ultimately fail?

Gosplan failed because of the knowledge problem—central planners lacked dispersed information about local conditions and preferences; perverse incentives meant enterprises prioritized meeting quotas over quality or efficiency; the system couldn’t adapt to technological change or shifting consumer preferences; and managers falsified information to meet impossible targets.

Did Gosplan ever succeed in achieving its economic objectives?

In early decades, Gosplan achieved rapid industrialization by mobilizing previously underutilized resources toward heavy industry. However, as the economy matured, growth rates declined and performance lagged behind market economies. Consumer goods remained scarce and low-quality, and technological innovation fell behind Western competitors.

What modern lessons can be drawn from Gosplan’s experience?

Gosplan demonstrates the importance of price signals and profit incentives for efficient resource allocation, the knowledge problem in centralized decision-making, the necessity of feedback mechanisms and adaptation, the dangers of perverse incentives, and why competitive pressure drives quality and innovation better than administrative directives.

How did Gosplan set prices if not through market mechanisms?

Gosplan set administered prices through central decree, often based on political considerations rather than actual scarcity or production costs. This created chronic shortages and surpluses, as the price signals that guide market economies were absent, preventing efficient allocation of resources.